Air trapped inside a blind adds to its R-value

If you want to increase the R-value of your windows, insulating window blinds are a good way to go. You won’t have to replace existing windows and you’ll get an attractive insulated window covering into the bargain.

Most blinds, if properly sized and installed, provide a layer of inert air between the blind and the window pane, which provides a small amount of insulation value. Air does flow through this area, but more slowly than if the window is uncovered, so there is less heat loss. The closer the window insulating blind edges are to the window edges, the less air flows and the less heat passes between the window and the room. (Remember, this helps give you more energy efficient blinds both in summer, when heat is trying to get inside, and winter, when it’s trying to escape.)

But most blinds just don’t do that much on the insulating side. They do help with direct heat absorption in the summer, by reflecting sunlight back outside before it can heat up your cool indoors. But they do very little in winter because that inert air really isn’t all that inert.

Insulating window blinds add an extra layer of insulation inside the blind itself. There are two main types of insulating window blinds. The first, dating to the 19th century, are simply roman shades made with several layers of fabric, so that heat has to pass through each layer of fabric and is therefore slowed. The second type of window insulating blinds, a much more recent invention, are cellular or honeycomb shades, which have horizontal (or occasionally vertical) columns of air trapped between two or more connected layers of blind. On horizontally oriented cellular insulating window blinds these air columns are virtually inert, although they are open at each end, because there is very little natural airflow side to side. On vertically oriented cellular shades, if both ends are open the cells do not provide very good insulation because heat naturally rises, which pushes warm air out the top and draws cooler air up into the bottom.

Roman shades as insulating window blinds

Roman shades can make inexpensive insulating blinds for windows. They are simply cloth window coverings consisting of several sandwiched layers of fabric that cover your windows when extended, and can be pulled up and out of the way using a system of string and loops.We had roman shades installed in our dining room five years ago (we bought them through a silent auction purchase and they were made by a local craftswoman). They look great since we were able to choose a fabric that goes perfectly with our dining room decor, and we felt good about supporting a small local business. Chances are there’s someone in your area who does this for a living, so why not ask around?

Still, custom-made insulating window blinds can be costly, so if you’re trying to save money both on your energy consumption and on the insulating window coverings you put in, you might consider making your own roman shades.

If you’re at all handy with a sewing machine you can make them for just the price of the fabric and thread, and a little hardware available from most building centers.

Terrell Sundermann teaches you exactly how to create window hangings, her combination of a wall hanging and a roman shade. This book gets great reviews from customers

and is written in clear prose with excellent illustrations.

Cellular shades

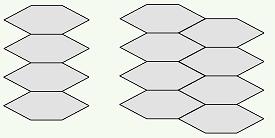

These insulating window blinds have evolved over the last couple of decades. The first insulating cellular shades were single-honeycomb structures: picture a series of hexagons stacked vertically, with the bottom side of one hexagon connecting to the top side of another. When the shades are pulled in, the hexagons collapse and take up very little space; when they are extended, the hexagons draw in air from the sides, which then stays relatively still.

Single and double hexagon cross-section

The more you can compartmentalize the air in a space, the better the R value of the space. That’s part of why foam insulation works more effectively than an empty air space, and for this reason shade manufacturers came up with the double honeycomb or double hexagon cellular shade design for their insulating blinds for windows, where two vertical stacks of honeycombs are staggered. This means that one stack of hexagons is thermally connected to the window area, and another to the room, rather than one stack connected to both. As a result thermal transfer is slowed down.

What is the insulation value of insulated window blinds? Single honeycomb shades have an insulation value around R-2, while double-layer honeycomb shades can reach R-5. They can block up to 62% of the heat transfer through the window.

Another design, the Duette Architella by Hunter Douglas, involves putting one hexagonal cylinder inside an enclosing one. In the opaque configuration intended to block sunlight flowing through the blind (where the inner honeycomb is made of opaque mylar), these insulated window blinds achieve an insulation value of R-7 or higher.

The only problem with honeycomb or cellular shades is that, while they provide much better insulation than a standard blind, they don’t allow you to finely control direct sunlight entering the room. It’s convenient, particularly in summer, to be able to choose between good insulation characteristics (e.g. when it’s really hot out and sun is shining directly on the window) and moderate lighting. With a regular blind you have little insulation but you can angle the vanes of the blind to different levels in order to let in no light, indirect reflected sunlight (if the vanes point down towards the outside) or direct sunlight (if the vanes point up). There’s just no way to do this with a shade (which is one continuous surface, unlike a blind which is made of slats).

One type of insulating window blind that provides good R value is made of airfoil-shaped vanes. These vanes can be filled with foam insulation (to increase the R value over what you would get with just air) and when closed, the insulation thickness corresponds roughly to the thickest part of the airfoil. When open, they allow about 3/4 of the light through directly and a bit more as light reflected off the foils themselves.

But cellular shades will provide better R value than these insulating window blinds if you don’t need to let direct light to enter.

Where to buy insulating window blinds

Most big box stores offer custom insulating window blinds, both made to order at the store, and by special order through some of the more reputable manufacturers such as Levolor. I would recommend avoiding the in-store blinds as they tend to be of lower quality and have very little R value, but a quality brand like Levolor is worth looking into. Our ground floor blinds are all Levolor honeycomb blinds bought at Lowes. They are top quality and when we did have mechanical problems with one of the blinds, about two years after purchase, we took it back to Lowes and the Levolor team replaced that blind with a working one within two weeks.

Another option is to buy your blinds online. Again, be careful where you buy. Some of the budget blind outfits offer deep discounts but quality tends to be poor. You can also buy standard-sized blinds on Amazon.com but most are standard sizes, which makes it harder to get a perfect fit inside a window frame and therefore reduces the energy efficiency of the blinds.

The best option is to have a blinds consultant visit your home, and purchase blinds through them. They will offer the widest selection of blind materials, their products are generally higher quality and backed by better warranties than what you’ll find at online sites or your big box store, and they do all the measuring for you so you know you’re getting blinds exactly fitted to your windows.

Combine insulating window blinds with curtains

We use a combination of window blinds and curtains in our bedroom bay window. This works great; the window blinds are translucent, allowing some light to pass through the mylar even when closed. This means we can block out the summer heat or keep it indoors in winter, but we still get enough natural sunlight into the room to be able to find our way around when we come looking for something. If we want to completely block out the sunlight (so we can sleep in on the weekend for example, or block out the city lights at night) we close both the blinds and the dark curtains, which are floor-length. The curtains help trap the air within the entire bay window area. In effect we have two layers of insulation: a thin layer between the blinds and the windows, and a much thicker (but more free-flowing and less effective) layer between the blinds and the curtains.

Looking for noise reduction?

Don’t forget that insulating window blinds can be more effective at cutting noise entering your room from outside, than standard curtains or blinds. The trapped air pockets in celluar shades, and the several layers of sandwiched fabric in insulating roman shades, are more effective at muffling outside sounds than standard vaned mylar shades or cloth curtains. If you’re a light sleeper like me, or a daytime sleeper who keeps getting woken up by the kids playing in the neighbor’s back yard, you can justify getting energy saving window blinds or shades for two reasons: cut your heating and cooling costs, and sleep more soundly!

I have very thick walls at 9″, as a result my window sills are about 8″ deep. I need to know if I will get better insulation by installing them closer to the window or more at the front of the window box so that the blinds are almost flush with the wall. I can see benefits to both, but wanted to ask if any one has data that shows one is better than the other.

The US DOE recommends having blinds fit as close to the window as possible and claims this leads to the greatest energy efficiency, but they don’t seem to provide any evidence to back this up. And of course the same information gets repeated on other websites.

For a deep sill like yours, assuming there’s no difference in the airgap around the blind edges regardless of how close to the glass you put them, my hunch (not data-driven) is that if the gap is small (under a quarter inch), the further from the window the better, because you have a larger air pocket providing extra insulation. However, the R value of an air cavity between 1/2″ and 4″ is considered to be R1 regardless of thickness (per http://www.coloradoenergy.org/procorner/stuff/r-values.htm and other sites) so it may indeed not matter from an insulation perspective.

A larger air pocket actually means there’ll be more air convection going on. There’s a reason why double and triple glass windows have such a small gap – to limit air convection.

I would put the blinds as close as possible to the window.

Guilaume is right. In double glazed windows the “air” gap has been getting bigger over the years as this is filled with insulating gasses (I.e, is not air), such as approach reduces conduction of heat. But as the gap gets bigger convection becomes the dominant heat transfer mechanism, and this is why double glazed windows have stopped getting bigger gaps. In summary, I would put it near the window.