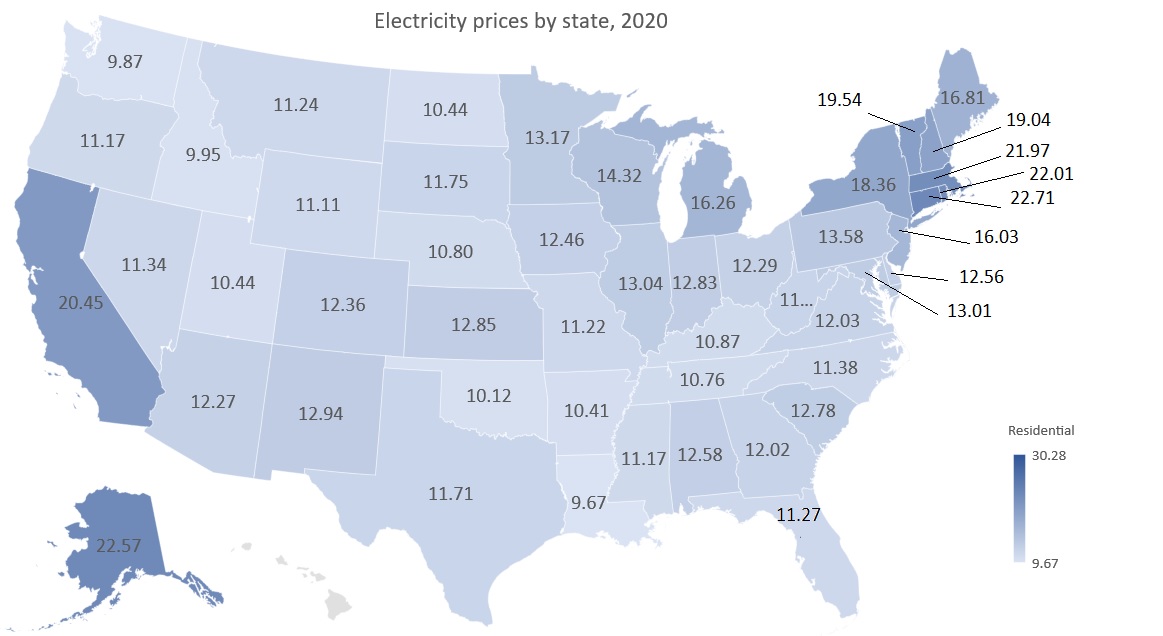

What is the average price by US state?

How much does electricity cost? It depends where you live. In the US, the highest electricity prices as of 2020, the latest year for which the Energy Information Administration makes data avalable, are in Hawaii, with an average residential cost of $0.30 per kWh (while that sounds like a lot, it’s only 2 cents more than it was 13 years earlier!). Connecticut and Arkansas are next in line at around $0.23 per kWh each, while Washington, Idaho and Washington State are the cheapest, at around $0.10 per kWh each (also only 2 cents more than 13 years ago).

The following map shows how much does electricity cost for each state. The redder the state the more expensive residential electricity, while states shown in green tend to the cheap end of the scale.

Unfortunately, some of the cheapest states for electricity prices are ones where a large share of their power comes from local coal deposits or imported coal. For example, among the ten cheapest states, 6 produce over 10,000 gigawatt hours of electricity from coal. Texas, while not among the cheapest ten (at 11.71 cents per kwh – so not too far off) burns a whopping 85,337 gigawatt hours of coal – that’s the equivalent of rougly 85,337,000 tons of CO2 emissions! Meanwhile, among the most expensive states, coal accounts for 20,361 gigawatt hours in Arkansas, but the other nine are all under 1,000 gigawatt hours. (Seven states use no coal at all in local generation).

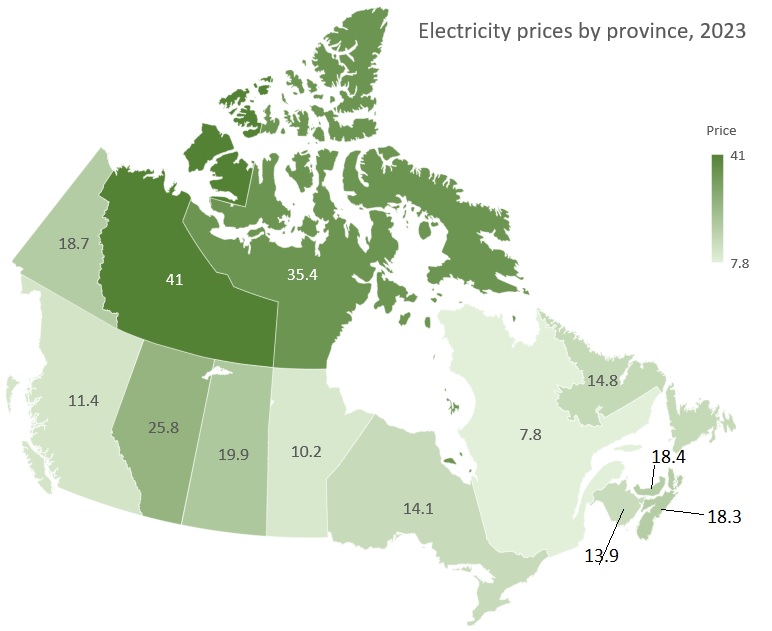

Electricity in Canada is generally more expensive than in the cheaper US states, with prices cited ranging from a low of $.07 CAD per kWh in Quebec (0.8 cents more than 13 years ago!) to a high of $0.35 CAD in Nunavut (odd that the hottest US state and the coldest Canadian territory have the most expensive electricity).

In some parts of Canada the price you see quoted is only part of the equation. For example, in Ontario where I live the price of electricity is made up of four separate charges:

- The electricity itself, at time of use rates of:

- On-peak: 15.1 cents per kWh

- Mid-peak: 10.2 cents per kWh

- Off-peak: 7.4 cents per kWh

- The delivery charge, at 8.4 cents per kWh

- The regulatory charge, at 0.57 cents per kWh, to cover the cost of regulating the electrical utilities

- Harmonized sales tax (combined Federal and Provincial sales tax) at 13%.

There’s also an “Ontario Electricity Rebate”, which is an absurd program to reward people for using electricity – the more you use, the more you earn. In theory it helps with the high cost of energy; in practice it discourages conservation. It also means Ontario taxpayers foot the bill, since the money doesn’t come from nowhere.

All told, the actual cost I pay my local utility is about 18.3 cents per kWh in Toronto, while the estimates provided by the National Energy Board and various other online sources have estimates of about 14.1 cents. In other words, not everything you’re paying is in the quote you get.

Then there’s the added cost of green electricity: for an added monthly fee, one can get EcoLogo certified green energy from Bullfrog Power, a local green energy provider (with service for residents of Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island). They source all their energy from small-scale hydro, wind farms, and other renewable sources. I was a customer for many years, but when I installed solar panels on my roof I decided I didn’t need more green energy.

How much does electricity cost in Europe? The average price in all of Europe for 2023 is 0.2335 Euros per kWh (excluding taxes). Prices in Europe range from a low of 0.06 Euros in Kosovo (an outlier – the next cheapest is France at 0.18 Euros) to a high of 0.45 Euros in Ireland.

Is expensive electricity a bad thing? Not at all. Higher electricity prices are the direction we should be going. The more electricity costs, the more people are motivated to conserve energy, whether by upgrading to more energy efficient appliances, using appliances or lighting less often, or trying to shift electrical use to times of day when electricity is cheapest.

Time of use charges also affect how much electricity costs. More and more utilities are moving towards either market pricing or time-of-use pricing (which is designed to give a very rough approximation of market pricing). Prices for electricity on the open spot market change minute to minute based on supply and demand. For example, during working hours the additional electrical load due to commercial and manufacturing use drives up both demand and supply (and usually drives demand up more than supply, resulting in higher prices), while in the middle of the night demand is typically low. In winter, when electrical heating tends to kick in the most in the early morning and evening as people wake up, or get home from work, the peak price is actually mornings and evenings, not the middle of the day. I’ve provided the prices a few paragraphs up – the times are typically 7-11am (peak in winter, mid-peak in summer), 11am-5pm (peak in summer when it’s hottest, mid-peak in winter), 5pm-7pm (same as 7-11am) and 7pm-7am (off-peak).

The intent of this pricing is to encourage people to avoid using appliances that draw a lot of power during peak periods – for example air conditioners in summer, electric heaters in winter, and large appliances such as electric dryers or dishwashers at any time of year. This is why many appliances are now sold with timers on them so that they can be set to start running several hours after you set them.

To cut your peak-period electricity use on heating in winter (assuming you heat with electricity), you can crank up the heat when electricity is at its cheapest (overnight) and then turn it down at 7am. Unfortunately people tend to prefer cooler temperatures for sleeping than for being up and about at home, but if you can capture that heat – either through a thermal storage heater or by having lots of thermal mass inside your home – it may be a better deal to turn the heat up at night and then let that thermal mass spread its heat through the house during the day. Unfortunately adding a large thermal mass is not that easy. You could fill hundreds of 2-liter pop bottles with sand or (even better) water, or you could put lots of extra decorative statues in your living area. The best way to get a large thermal mass in your home is to include it in the design of a new home. Many passive solar homes have large masonry walls or floors inside the home to absorb sunlight (or other heat) during the day in winter, which they then slowly release at night. Of course, if you’re building a passive solar house you will want to build it as a zero energy home, in which case you won’t need much additional heat at all – a zero energy home can be heated even in very cold climates with no more heat than that put off by a single blow dryer.

In summer you can cut your peak use from air conditioning by making the house very cool starting at 9pm, and then setting your thermostat much warmer during mid and peak hours. If you keep your windows closed as well as curtains and blinds, you can keep the house cool for many hours after the air conditioning has been shut off.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!